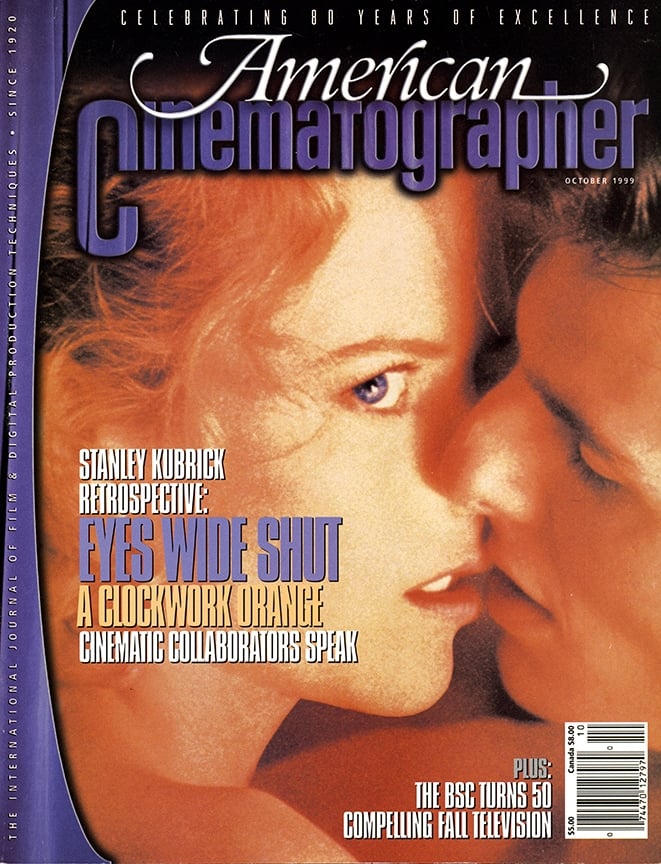

A Sword in the Bed: Eyes Wide Shut

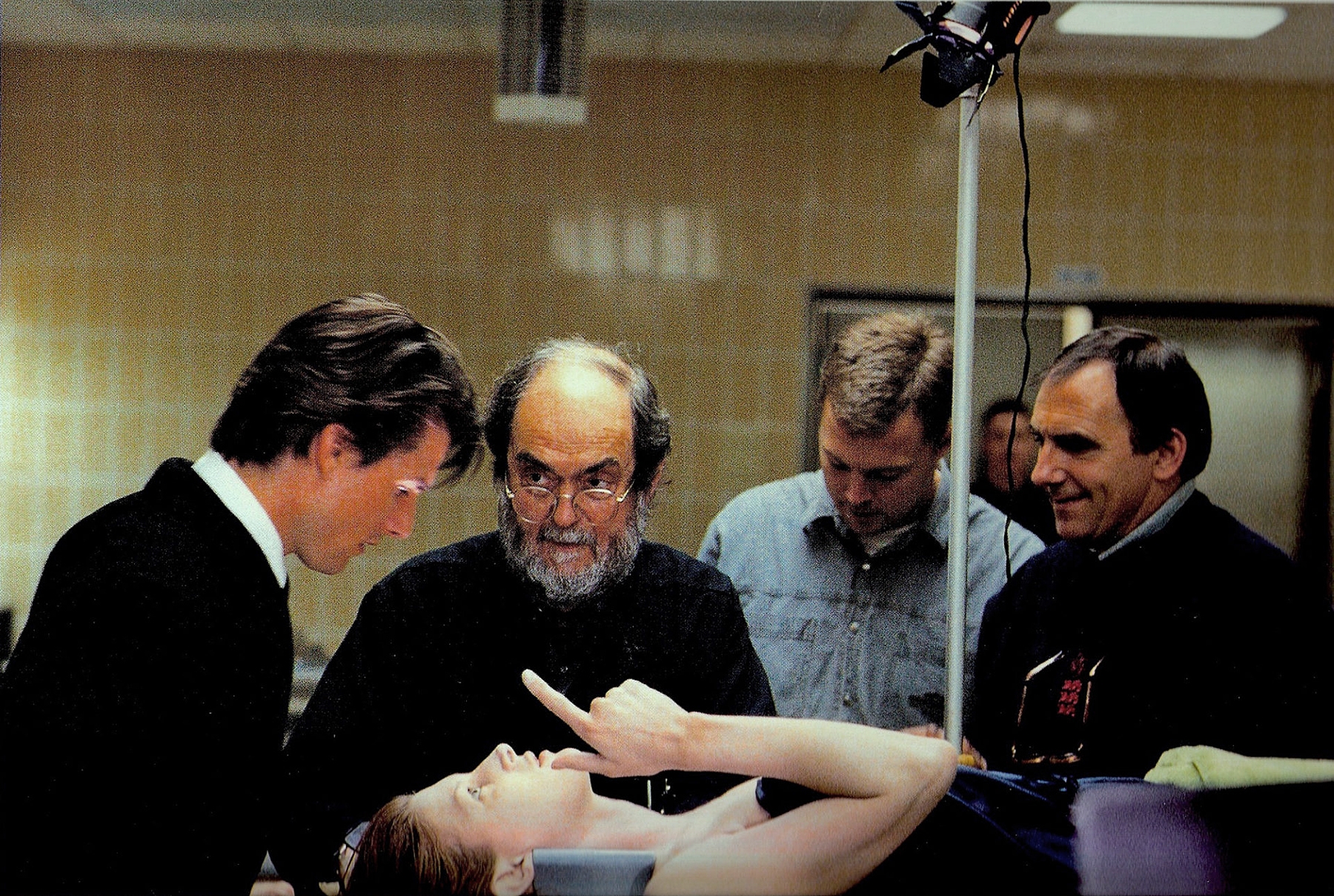

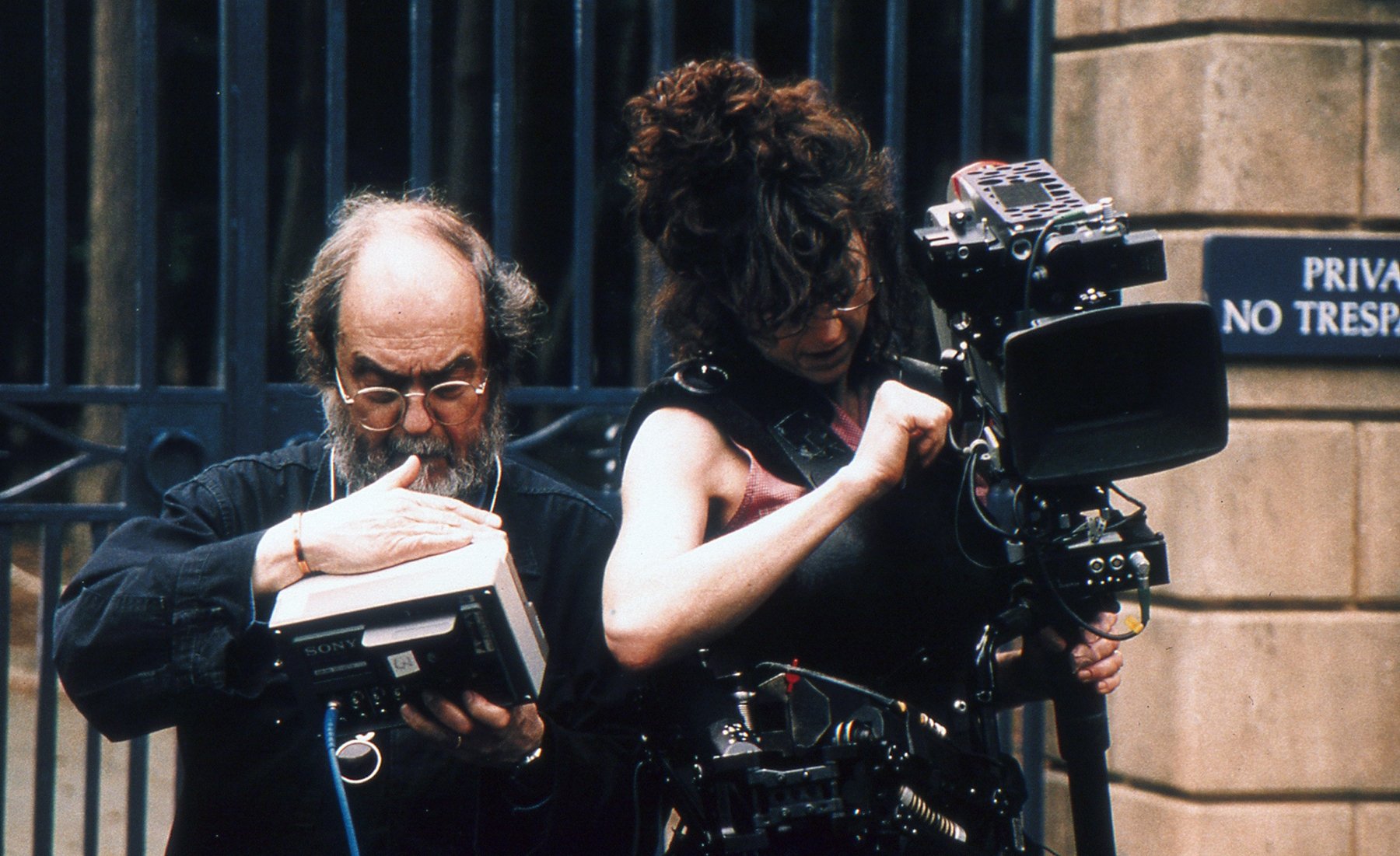

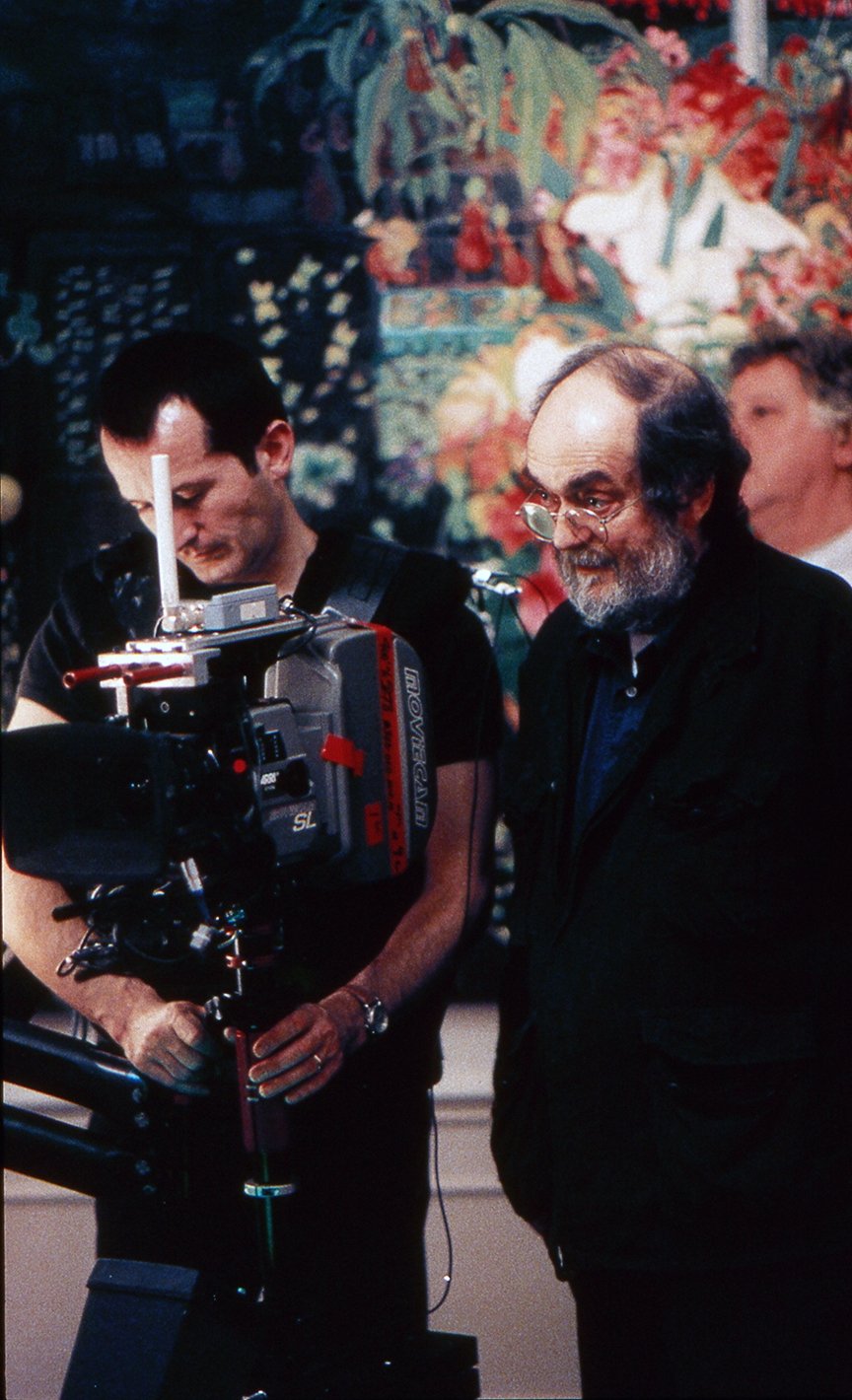

Cinematographer Larry Smith helps Stanley Kubrick craft a unique look for this dreamlike coda to the director’s brilliant career.

Unit photography by Manuel Harlan

In Viennese author Arthur Schnitzler's Traumnovelle (Dream Story), a seemingly happy marriage is nearly torn asunder when a prominent physician learns that his faithful wife has strayed in her imagination. Stunned by his spouse's confession, the good doctor suffers Freudian feelings of emasculation that send him spiraling off on a compulsive quest for sexual validation and revenge. He wanders the nighttime streets, determined to regain his pride, and soon meets a succession of temptresses who steer him toward a reunion with an old college classmate — a failed medical student who earns his living playing the piano. When the musician reveals that he occasionally plies his trade at masked orgies staged by wealthy and prominent citizens, the doctor insists on infiltrating that very evening's event, consequences be damned. Once he gains entrance, however, a sinister twist of fate threatens to derail both his marriage and his sense of security.

Schnitzler's novella, penned in 1926, fascinated legendary director Stanley Kubrick for several decades. The filmmaker finally took his first serious step toward adapting the material in 1994, when he began collaborating with noted screenwriter Frederic Raphael, who had earned an Academy Award for Darling (1965) and a nomination for Two for the Road (1967). Convinced that male-female relationships hadn't changed a great deal since Schnitzler's era, Kubrick told Raphael that he wanted to update the writer's tale, which was set in 19th-century Vienna, to present-day New York.

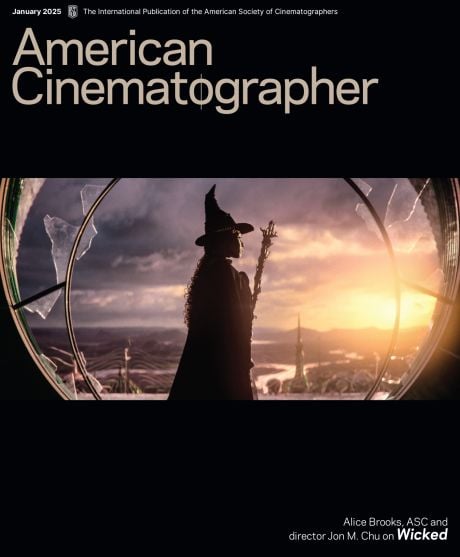

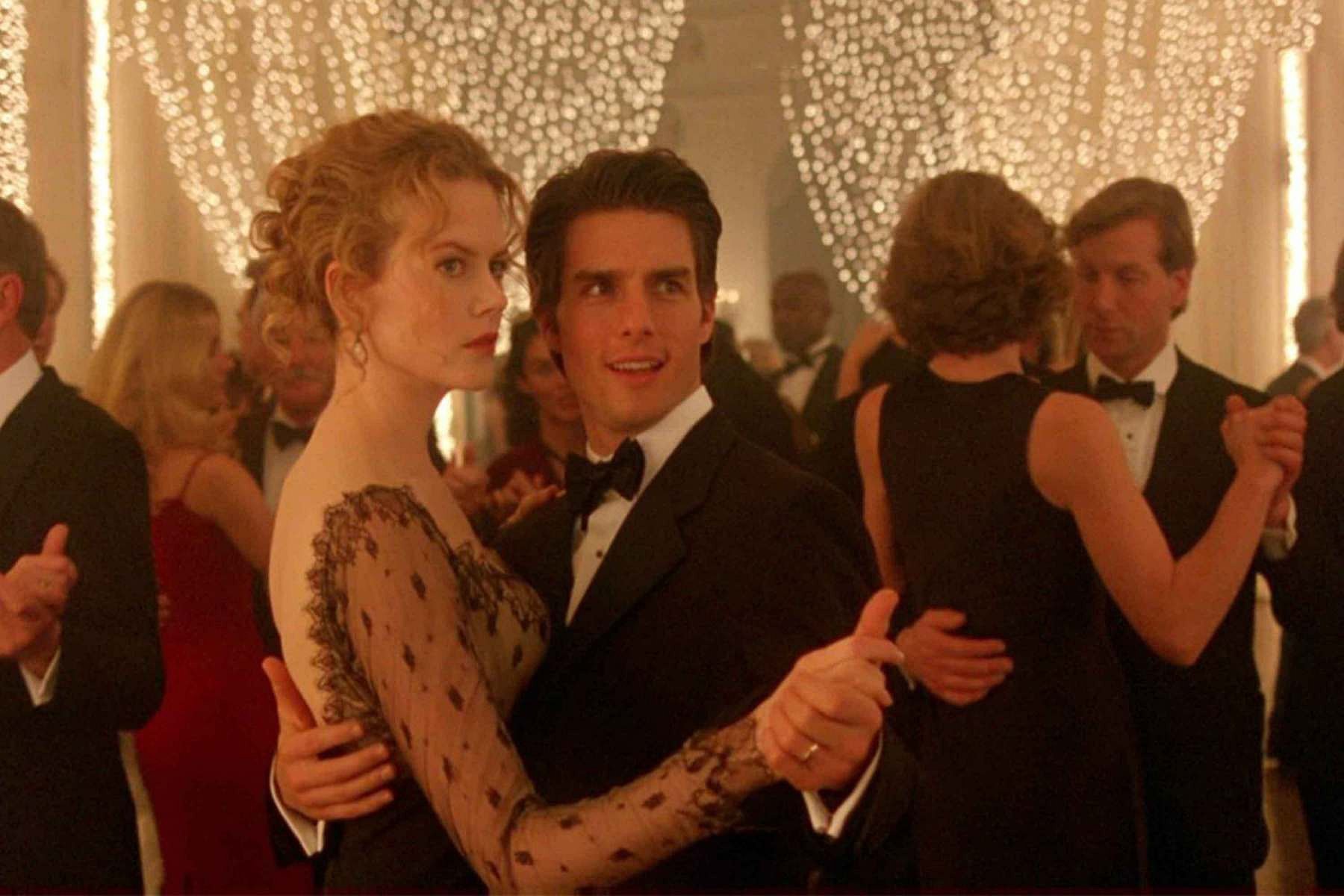

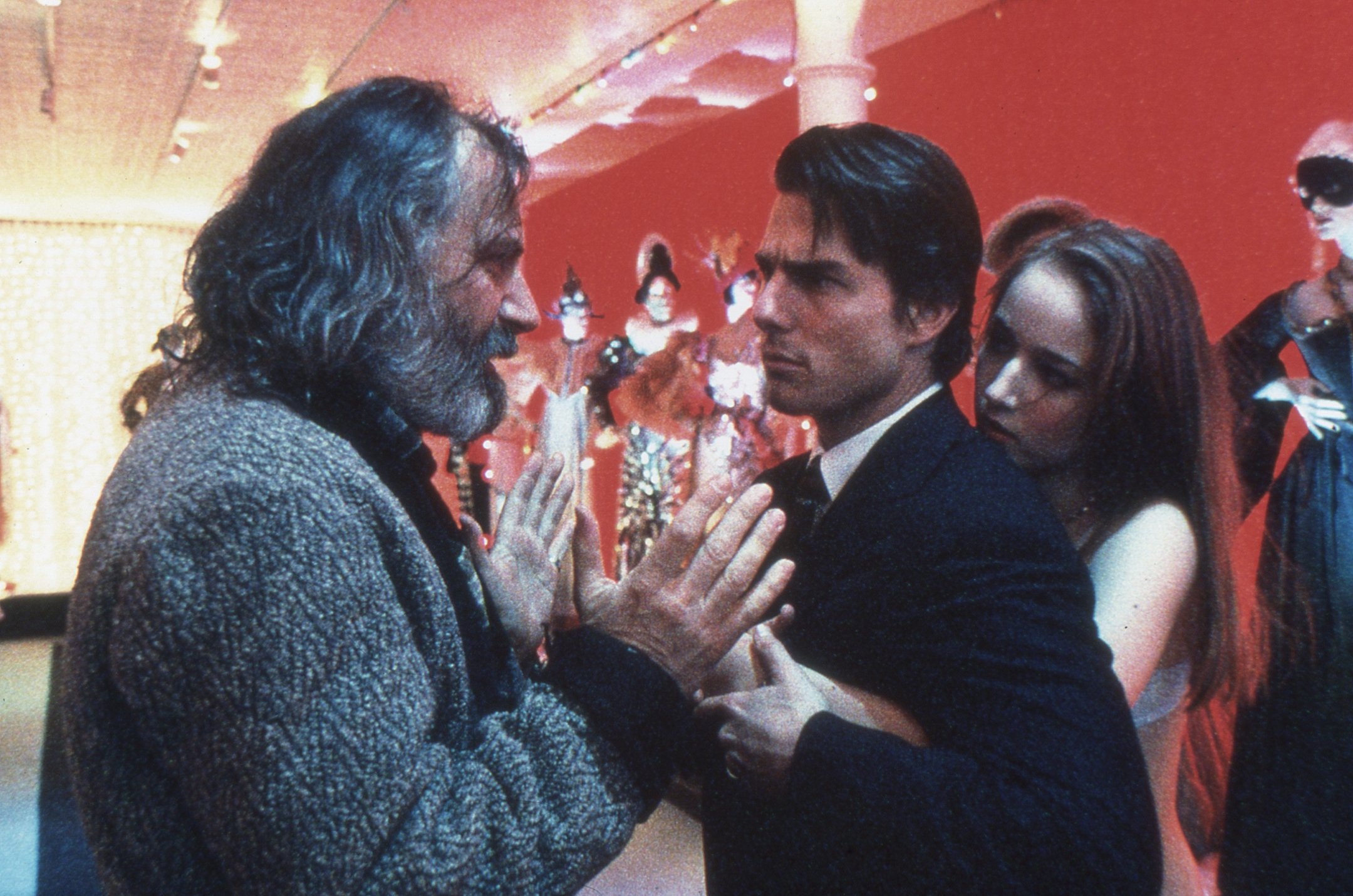

The duo hewed closely to their source material, fashioning a dreamlike tale of sexual obsession that became a star vehicle for married actors Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, who were recruited to play Dr. William Harford and his artcurator wife, Alice. Production of the film began in November of 1996, and proceeded at a pace that could only be described as unusually deliberate, even by Kubrick's standards. The film was finally completed in March of 1998 and released this past July, just four months after the filmmaker's death.

Renowned for his exacting standards and perfectionist tendencies, Kubrick labored over every detail of the film — right down to the set dressings, which included paintings by his longtime spouse, Christiane. Famously unwilling to travel far from his home base in Hertfordshire, England, the filmmaker had elaborate Manhattan street sets constructed at Pinewood Studios. He also selected various other locations, including an estate in Norfolk that would serve as the site of the orgy, which ostensibly occurs on Long Island.

“Because I’d worked with Stanley before, I knew what kind of commitment he demanded. I knew it would be a long schedule and that I’d have to be wrapped up in the project body and soul.”

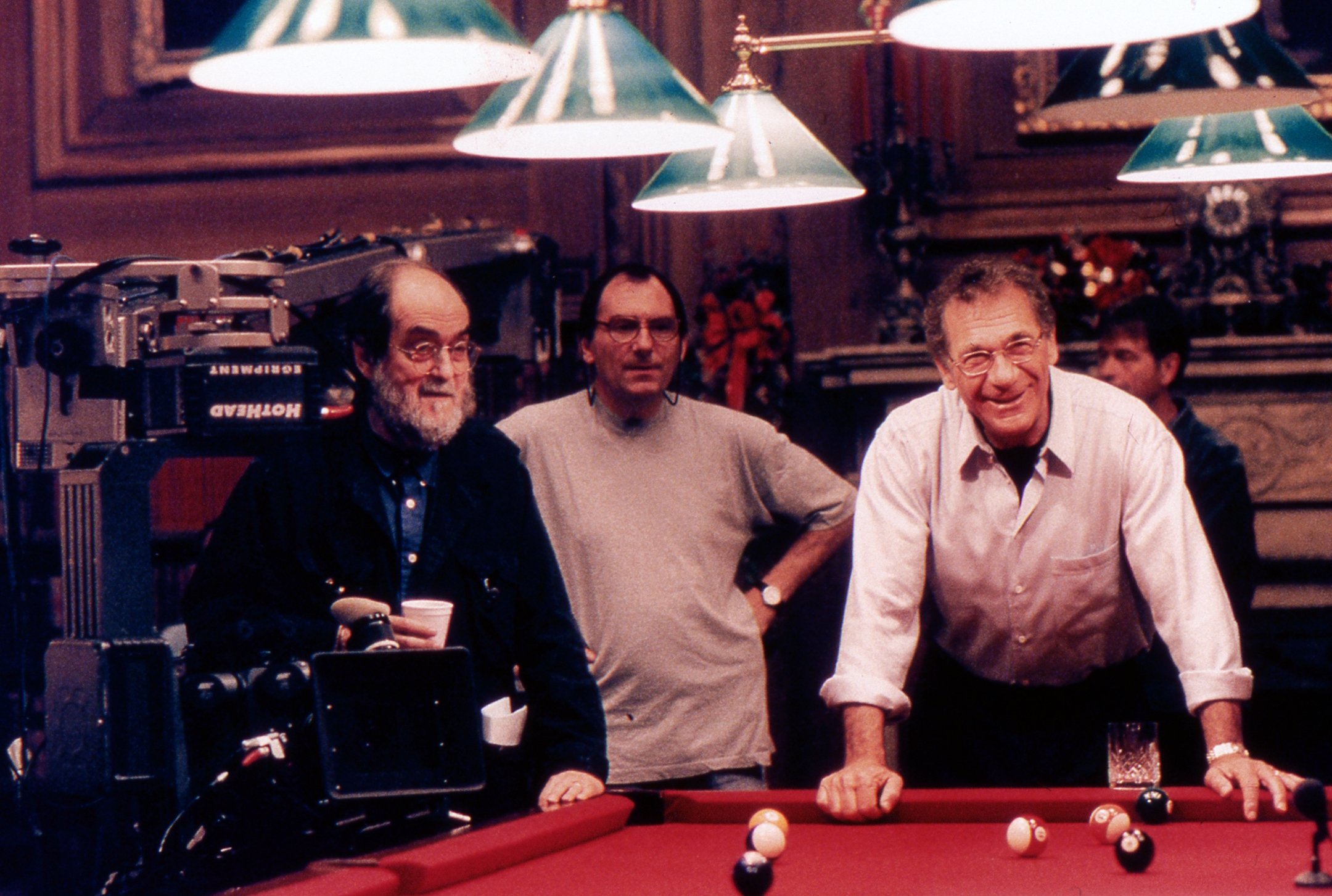

On one of these scouting trips, Kubrick brought along cinematographer Larry Smith, who had served as a gaffer on both Barry Lyndon and The Shining. The duo drove out to an estate that was being considered for the orgy sequence, and as they examined it from a distance, the director asked Smith how he would light the imposing edifice for a night exterior scene. After Smith detailed his strategy, the pair headed back to Kubrick's home. "When we arrived at the house, he said to me, 'Well, do you want to shoot the movie?'" Smith recalls. "It was as simple as that. This may sound strange, but I didn't say yes right away; I actually asked him if I could sleep on it! Because I'd worked with Stanley before, I knew what kind of commitment he demanded. I knew it would be a long schedule and that I'd have to be wrapped up in the project body and soul. Of course, deep down I knew right away that I was going to do it, and I told him so the next day. Obviously, most cameramen would give their right arm to work with Stanley, but ultimately, the reason I said yes was because we'd been friends for more than 20 years, and he asked me personally if I wanted the job. That meant a lot to me.”

Smith's association with Kubrick began in the early 1970s, when he was asked to serve as chief electrician on Barry Lyndon. Smith had carved out a career in exhibition lighting, but he had repeatedly found himself drawn to feature filmmaking, and he jumped at the chance. "At the time, I didn't really know too much about Stanley,” he admits.

"I knew he was an American movie director whose films had been very well-received. As soon as I began working on the show, though, I realized that Stanley was not an ordinary person; he had tremendous vision, as well as a unique and very charismatic presence. His personality was quite understated, but when people were around him, they didn't know quite how to comport themselves. They definitely became intimidated, even though he never resorted to tactics like shouting, screaming or footstamping. Rather, their uneasiness stemmed from the fact that he was a very smart man who asked intelligent and searching questions. Interacting with Stanley was a bit like playing tennis with a professional; if you were quick enough, you could hit the ball back to him, but if you weren't, you wouldn't last long.”

Smith himself managed to return Kubrick's serve during a day of interior shooting on Barry Lyndon. The production was set up in one of the film's stately manors, but it was raining heavily outside, where the crew had set up an array of Mini-Brutes on towers to illuminate the scene through the building's windows, which were covered with tracing paper. "Things were going a bit slowly, and I was discussing the situation with the director of photography, John Alcott [BSC],” he remembers. ''All of the lighting gear was mounted on metal platforms, and the crew was proceeding with caution. Up to that point, I hadn't had any personal interaction with Stanley, but he ambled over and said to me, 'It's raining out there, isn't it?' I told him it was, and he asked, 'Is it dangerous?' I answered, 'Well, that's what they're saying.' He replied, 'You're communicating with the crew, so they've obviously got radios, right? Aren't the radios getting wet?' I told him, 'No, they aren't, because we wrapped them in polythene bags.'

“[Stanley] consumed a lot of books and journals, including American Cinematographer, which he read religiously — he was always waving the magazine under my nose to see if I’d read this or that article.”

"Well, that's just what Stanley wanted to hear, and from that moment on, we got along famously,” he says with a laugh. "I had a very happy friendship with him right up until he died.”

Asked to outline Kubrick's methodology on the set, Smith compares the director to a field general in the military, noting that "any general worth his salt knows that he has to have very good officers down through the ranks. Stanley wanted everybody on his projects to really know what they were doing; he needed to have complete confidence in the people around him. When you're working on a film as big as Barry Lyndon, with the vastness of the locations and the splendor of it all, you quickly realize that none of it happens by accident — everything has to be very carefully thought-out and choreographed. Stanley had a lifelong fascination with Napoleon Bonaparte, and if he hadn't been a committed pacifist, I think he would have made a great military strategist, because he was very organized and good with logistics.”

Smith confirms that Kubrick was "totally absorbed" by his craft. "When he was working on something, he focused on it completely — he couldn't think about anything else. He did a tremendous amount of research, which is probably why he didn't make as many movies as some other filmmakers. In fact, he did quite a bit of the research himself — obviously, he would also get other people to gather certain bits of information for him, but if you gave him a slab of material, he'd go through it and ask a barrage of relevant questions. He consumed a lot of books and journals, including American Cinematographer, which he read religiously — he was always waving the magazine under my nose to see if I'd read this or that article. If there was a new tool out there, he knew all about it, even though he didn't necessarily have hands-on experience with it. For that reason, he had no preconceptions about what a piece of equipment could do. He'd simply say, 'Well, let's get it and try this or that with it.’

“Stanley’s views about actors are quite well-documented. With certain actors on his previous pictures, I think he probably felt that he needed 70 takes to get them to do the scene properly! It wasn’t like that with Tom and Nicole, however.”

"During all of this research and testing, Stanley would gradually get an overall picture of what he wanted to do, how he wanted to do it, and where he wanted to do it. He had a great deal of foresight, and he didn't restrict himself to a particular mode of working. He created a new style every time he did a movie, and along the way, he invariably came up with some incredible ideas.”

When filming was imminent, Smith says, Kubrick would obsess over every visual element that would appear in a given frame, from props and furniture to the color of walls and other objects. "Stanley would tell the production designers and set dressers exactly what types of lamps, chairs or decor he wanted, and he always preferred using the best materials — he wouldn't use paper and wood if it was possible to do it with plaster, cement or brick. If we didn't like the color of the walls or something else in the scene, he'd have them changed.

"Once the sets were built, I'd go in and light them. I'd get the electricians in there, set up all of the practical lights, and then wire them to dimmers to give us the control we needed. After everything was in place, I'd shoot various tests with different exposures. When we looked at the test footage, Stanley would say things like, 'I like that, I don't like that; 'Why don't we try this?' or 'Why don't we go and shoot some more tests?' A typical comment might be, 'I don't like the look of that lampshade, let's change the color: The process involved a constant series of adjustments, which is one of the reasons that our schedule was so long. In many ways, it's a much more expensive and time-consuming way to shoot than simply using lights to achieve a certain color scheme, but that's the way Stanley worked on all of his movies. He was never afraid to go back to a certain set or location and change things around. He wouldn't show even a single frame of film that he wasn't happy with himself. When the paying public goes to see a Stanley Kubrick film, they're not going to get something that's simply thrown together.”

Smith and his crew would typically have a set completely ready the night before a given scene was scheduled to be shot. The next day, Kubrick would rehearse the actors for as long as he felt was necessary before rolling the camera. The cinematographer notes that Kubrick's reputation for multiple takes, while accurate, was often misconstrued as perfectionism taken to eccentric extremes. "Stanley's views about actors are quite well-documented,” Smith points out. "With certain actors on his previous pictures, I think he probably felt that he needed 70 takes to get them to do the scene properly! It wasn't like that with Tom and Nicole, however. We did occasionally do lots of takes, but it was more often due to a logistical problem than acting issues. Stanley didn't do take after take because he enjoyed it or wanted to drive everyone crazy — the scene was either right or it wasn't right, and whatever kept it from being right had to be eliminated. It might be something very subtle, like an ashtray facing the wrong way, but Stanley had a phenomenal eye for small details."

On Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick was inspired to work with existing light fixtures and a minimum of "movie lights" — a strategy he had previously pursued to stunning effect on both The Shining (see AC August 1980) and Barry Lyndon (which earned John Alcott the Oscar for Best Cinematography; see AC March 1976). While shooting the latter picture, Kubrick used a pair of special super-fast f0.7 Zeiss lenses (36.5mm and 50mm) to film candlelight scenes with virtually no supplemental lighting. The custom-made instruments were actually still camera lenses developed for use by NASA in the Apollo moon-landing program, later modified for Kubrick by Ed DiGiulio of Cinema Products Corporation in Los Angeles.

Smith reports that Kubrick actually asked DiGiulio to recalibrate the Barry Lyndon lenses for use on Eyes Wide Shut, but eventually scrapped that plan. "Stanley wanted to shoot with available light and real sources wherever possible;' Smith relates. "We discussed the idea of using the f0.7 lenses from Barry Lyndon, but they just weren't right for the type of shooting we were doing. Stanley wanted to be able to show some of the sets, such as the ballroom in the opening party sequence, in 360 degrees, via extensive Steadicam work and wide-angle lenses. He wanted to give the actors the flexibility to move wherever they needed to, and he also wanted to swing the camera around the room without worrying about where the lights were. Furthermore, Barry Lyndon was made more than 25 years ago, when film stocks were rated at 100 ASA. Now we have the luxury of 500- and 800-speed stocks, which eliminates the need for specialized lenses like those old f0.7 Zeisses.”

Kubrick framed Eyes Wide Shut in the standard 1.85:1 format, primarily using a set of Zeiss Super Speed Tl.3 spherical prime lenses, but occasionally opting to employ Arri's T2.1 variable prime lenses or a zoom. Smith notes that the auteur favored wider lenses to show off the production values in his sets; most of Eyes was shot with the Zeiss 18mm lens, and the filmmakers rarely went longer than 35mm. A longtime fan of Arriflex cameras, Kubrick deployed a pair of 535Bs, operated by Martin Hume, throughout the production. The filmmakers also made frequent use of a Steadicam rig equipped with a Moviecam SL, operated by either Elizabeth Ziegler or Peter Cavaciuti.

In order to facilitate Kubrick's shooting strategy, which required the picture's film stock to be force-developed by two stops at Deluxe Laboratories in London, Smith conducted extensive photographic tests at the prep stage. "Kodak's Vision 5OOT stock had just come out, but I was planning to use their old EXR 5298, another 500-ASA stock. During my tests, I discovered that while you can't really forcedevelop the Vision 5OOT, the old 5298 could handle it quite well, even if you were forcing it two stops. Kodak designs their stocks to be shot in the middle of the sensitometric curve, rather than at the extreme ends, and when I tried to force the Vision 5OOT, I found that it had a blue bias. Obviously, that's a characteristic of that particular stock, so we opted to use the 5298 instead. That gave us a bit of a problem, of course, because 98 had been phased out, but Kodak assured us that they could provide as many rolls of it as we needed.

"During our tests, we decided that we liked what we were seeing, although we were always debating various issues, such as 'What will force-developing do to the skin tones?' or 'How will it affect the practicals?' There's no question that with force-developing you get exaggerated highlights — they really blow out. We decided that if we pushed everything two stops, it would really have the effect of an extra stop and a quarter or a stop and a half. That's basically the way we worked it out, and we eventually decided to force-develop everything, even the day exteriors, to keep the look consistent.”

Smith credits Deluxe with making this strategy viable. ''I'd forced footage before for the odd shot, but never for an entire movie,” he says. "I quickly came to realize that it's not an exact science; you do get some variations, because it's very difficult to keep things within certain parameters when you're force-developing every frame on a project of this magnitude. Having said that, I think Deluxe did an incredibly consistent job day in and day out. They put aside a bath just for us, and they always put our stuff through first — that was a special privilege they extended to Stanley. It was a sevenday-a-week job to make sure that what we were getting was consistent, and I give all the credit to the guys who handled that. Ian Robinson was our main contact at Deluxe U.K., but the guy who supervised everything was their director of operations, Chester Eyre.”

Eyre, who first worked with Kubrick as a timer on A Clockwork Orange, began collaborating more closely with the director on Full Metal Jacket. He notes that Kubrick never limited himself to standard lab practices, particularly in the case of Eyes Wide Shut. "Stanley had his own ideas about what each picture should look like, and what he was trying to achieve with it. Before he began shooting Full Metal Jacket, we talked about the look quite extensively. He detailed the lighting style he was planning to use, and we did lots of tests. On Eyes Wide Shut, he told me he was going to rate the negative stock faster than the actual recommended speed, and that he wanted us to force-develop it two stops to bring it back to its original exposure level. That created several advantages for him: he could work with less light and obtain a particular mood. Force-developing in that way is very unusual, and it's normally done as a last resort if the filmmakers are losing their light and are desperate to get a shot. On this picture, though, it was a deliberate strategy that was designed to get a special look; we basically left the negative in the developing bath for a longer amount of time than usual.

"Lab people always worry when things are done in a non-standard manner, and at first we were all surprised that he wanted to do it. However, once we began seeing the results and the quality of the negative, we understood what he was trying to do. If you look at the night scenes in particular, they have terrific exposure and depth, as well as very good blacks.”

“We decided to shoot nearly all of the picture at a stop of T1.3, and since we were pushing everything, we were able to create a wonderful warm glow.”

The results of the two-stop force-development are clearly evident in the film's first major setpiece, an elaborate Christmas party staged at the spectacularly lavish home of Dr. Harford's top patient, multimillionaire Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack). During the course of the evening, both Bill and Alice are propositioned by predatory members of the opposite sex: as the physician is waylaid by a pair of seductive models (Louise Taylor and Stewart Thorndike), a tipsy Alice takes a spin on the dance floor with an unctuous Hungarian playboy (Sky Dumont). The scene was lit almost entirely with a huge wall of ordinary Christmas lights to create an elegant holiday ambience. "Two months before the movie went into production, we began testing for the party sequence,” Smith recalls. "We tried out a variety of different Christmas lights before I found the ones I wanted in a catalogue. They were very low-wattage, but had a really magical quality. The effect is obviously enhanced by the force developing, which made the lights appear to be much brighter than they were, but even to the naked eye, the visual impact of that setup was sensational.

"We decided to shoot nearly all of the picture at a stop of T1.3, and since we were pushing everything, we were able to create a wonderful warm glow. We also used a Tiffen LC-1 [low-contrast] filter for our night interior scenes, and the effect it produced is especially evident in the party sequence — it made the lights glow and gave everything a slightly surreal edge.”

Although the filmmakers used no additional lighting in wider shots of the party, Smith did modify his approach for close-ups of the actors, utilizing a China ball containing a dimmer-controlled 200-watt bulb. "The China balls were very useful if there was any movement in the scene, because they're very light; we could just walk around with them and do anything we wanted. Normally, I only used a small amount of fill light when things began to get a bit murky, because I knew that the force-developing would give us the exposure level we needed. For the scene in which the Hungarian first approaches Alice, I created some fill with a smaller curtain of the Christmas lights.”

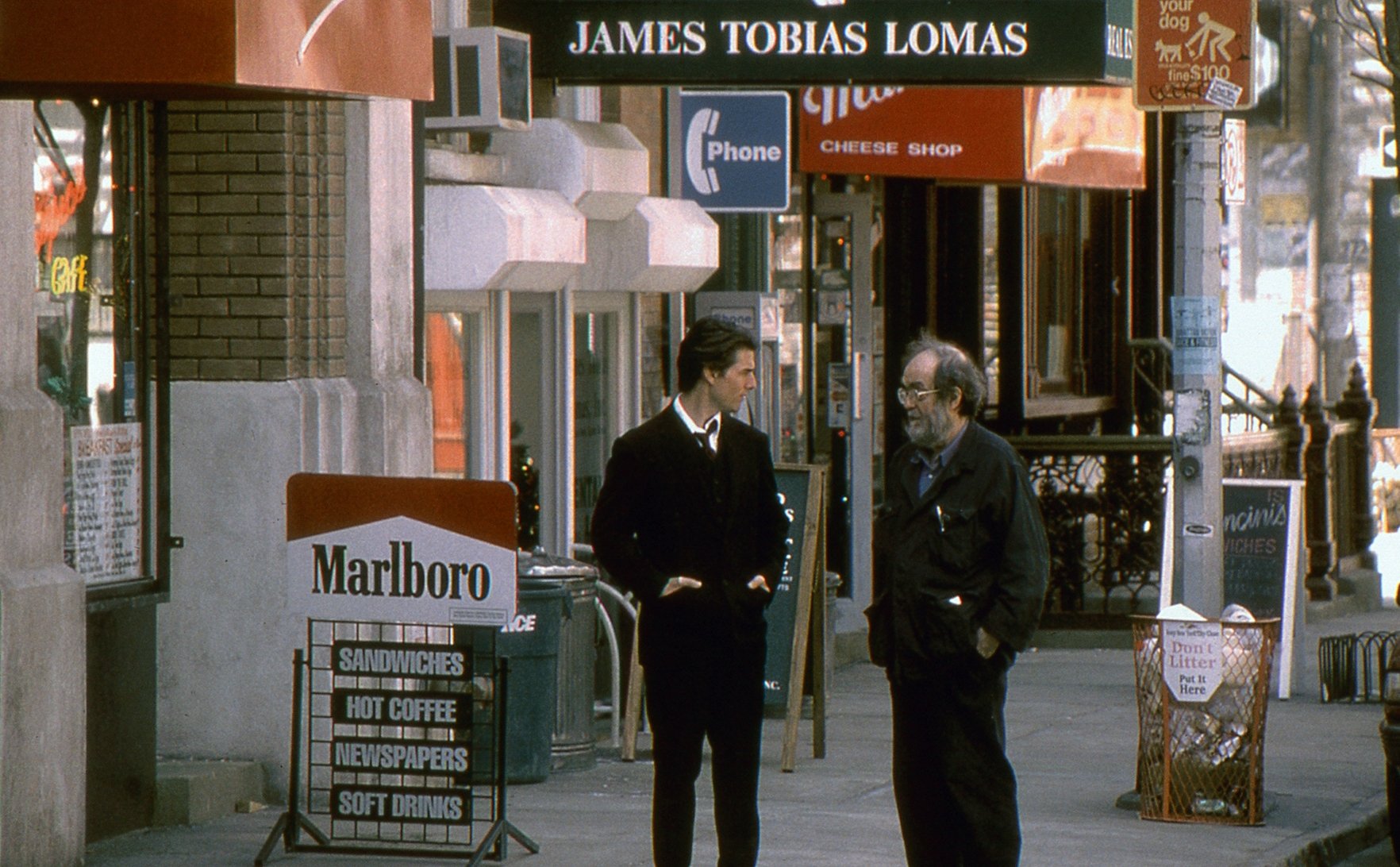

Smith found himself striving for a different type of nocturnal ambience when the production moved onto the highly detailed Manhattan street sets at Pinewood, which were built by a production design crew headed by Les Tomkins and Roy Walker. Four blocks' worth of facades were built and then dressed with street signs and other authentic items that were shipped in from New York City itself. The facades were periodically redressed, depending upon the scene at hand. "Once again, we used available light,” he details. "We put New York-type lamp posts right in the frame, and they were all on dimmers. They were ordinary lamp posts that we converted; we took out the normal bulbs and replaced them with our own 2K single-ended bulbs. To add a bit of light to the scenes, I'd usually turn up the levels on some of the lamp posts that were out of shot. We also placed a few 300- or 500-watt quartz bulbs on the buildings, as well as a few other lights that we aimed downward to create pools of light. The rest of the illumination for those scenes was provided by Christmas fixtures and the lights we placed in the various shops and storefronts.

"We did shoot some of the street stuff on real London streets, and for those scenes I occasionally created an overall nighttime ambience with a big blue 18K fixture mounted on a cherrypicker. We didn't do that so much on our New York street sets, though, because the practical lights were usually enough to create a good atmosphere."

Smith notes that the filmmakers applied a classic trick in a rather unusual manner for a few medium shots of Harford walking restlessly along Manhattan streets. "In some of the scenes, the backgrounds were rear-projection plates,” the cinematographer reveals. "Generally, when Tom's facing the camera, the backgrounds are rear-projected; anything that shows him from a side view was done on the streets of London. We had the plates shot in New York by a second unit [that included cinematographers Patrick Turley, Malik Sayeed and Arthur Jafa].

Once the plates were sent to us, we had them force-developed and balanced to the necessary levels. We'd then go onto our street sets and shoot Tom walking on a treadmill. After setting the treadmill to a certain speed, we'd put some lighting effects on him to simulate the glow from the various storefronts that were passing by in the plates. We spent a few weeks on those shots.”

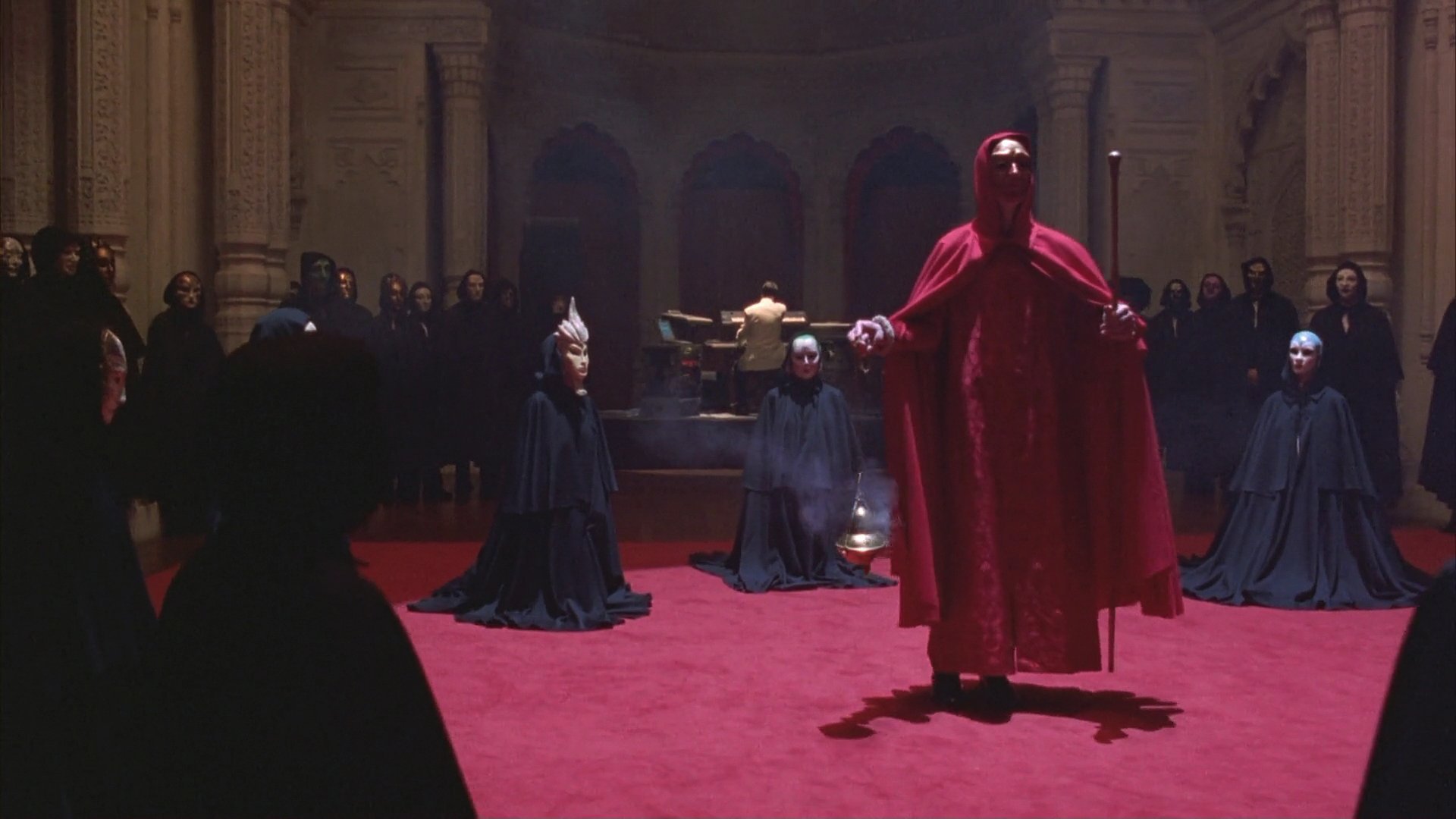

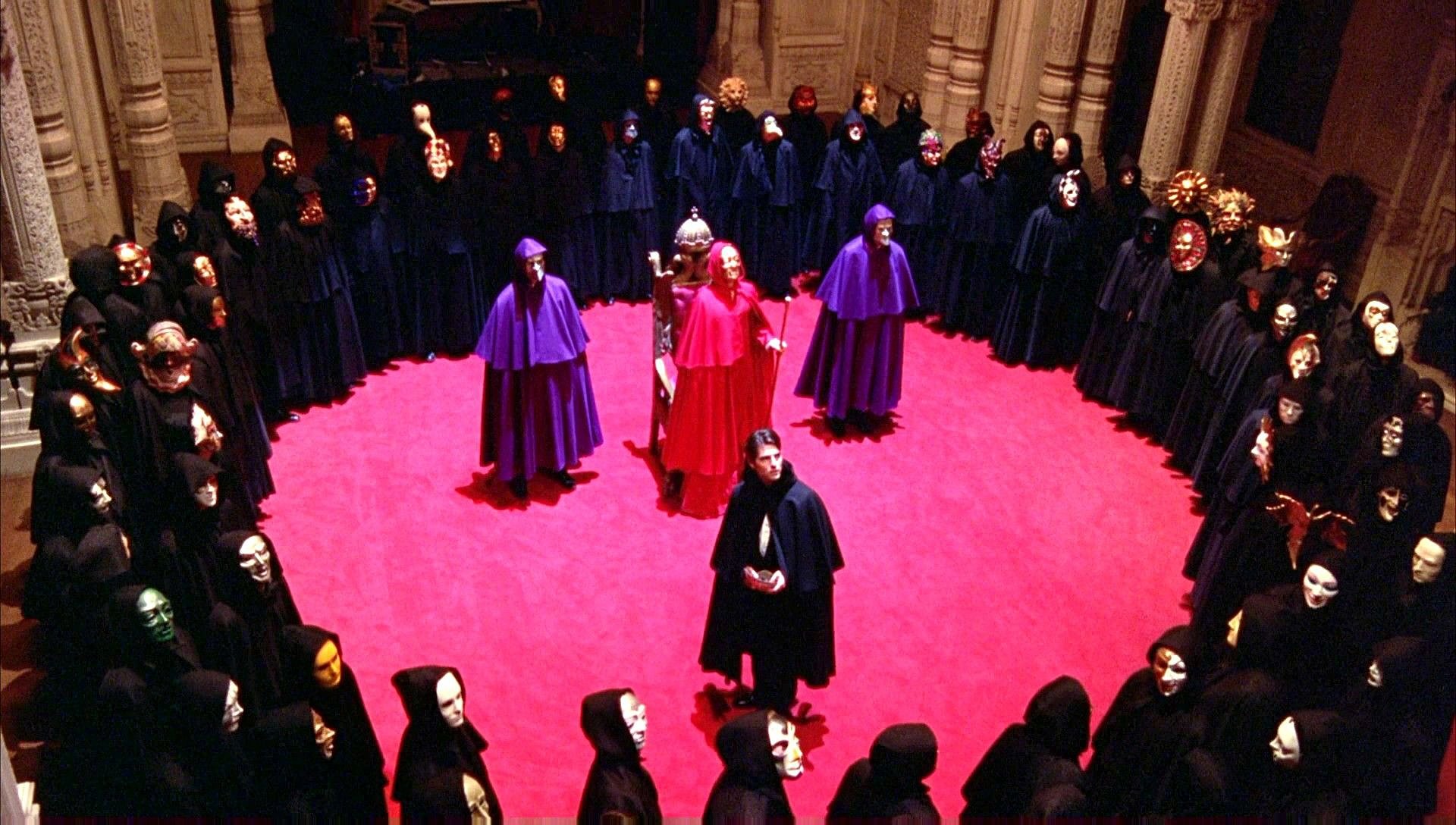

Eight more weeks were required to capture the film's visual centerpiece: a baroque, ritualistic orgy staged in an elegant mansion by powerful members of society's upper crust. Concealed beneath a mask and dark cloak, Dr. Harford watches in astonishment as an imposing red-robed figure consecrates a circle of nearly nude women, who then select partners from the crowd of costumed onlookers. The physician soon finds himself touring the mansion's many rooms, where the masked revelers engage in a salacious display of sexual abandon.

The sequence was shot in Norfolk, England, at an estate that featured an array of Indian architectural flourishes, including a very high, domed ceiling. "In order to light the mansion's main room, we installed a big truss rig up in the dome,” Smith explains. "Mounted in the truss was a Martin PAL 1200 unit, which we rented from a rock 'n' roll lighting company in London; it has a 1.2K HMI lamp inside that bounces off an adjustable mirror, and you can put different kinds of gobos in it. The truss also held a couple of Martin MAC 500s, which are from the same family of lighting instruments; we used those to light the people standing just beyond the ceremonial circle. To provide some overall fill, we set up some space lights as well. That was our basic setup in the main room, although I did use a couple of small spots for close-ups of the man in the red cloak.

"The shots where Tom's character begins gliding from room to room were done with the Steadicam,” Smith adds. "Once again, we used practical lights for those scenes. I also had some wooden plinths made, and we used those to hide some lights that raked up the columns in the rooms, so you'd never see a direct light. There were a few ceiling lights here or there, and a couple of wall lights, but that was it.”

In U.S. prints of the film, digital figures were added — at the behest of the Motion Picture Association of America — to obscure the most explicit action in the orgy sequence. Asked for his opinion on this controversial edict, Smith says simply, "Naturally, I'd have preferred if [the MPAA] hadn't required that, but Stanley had to comply in order to get an R rating. In Europe, the digital figures won't be there. Personally, I don't think it's that big a deal, but European viewers will certainly see much more going on in those scenes!"

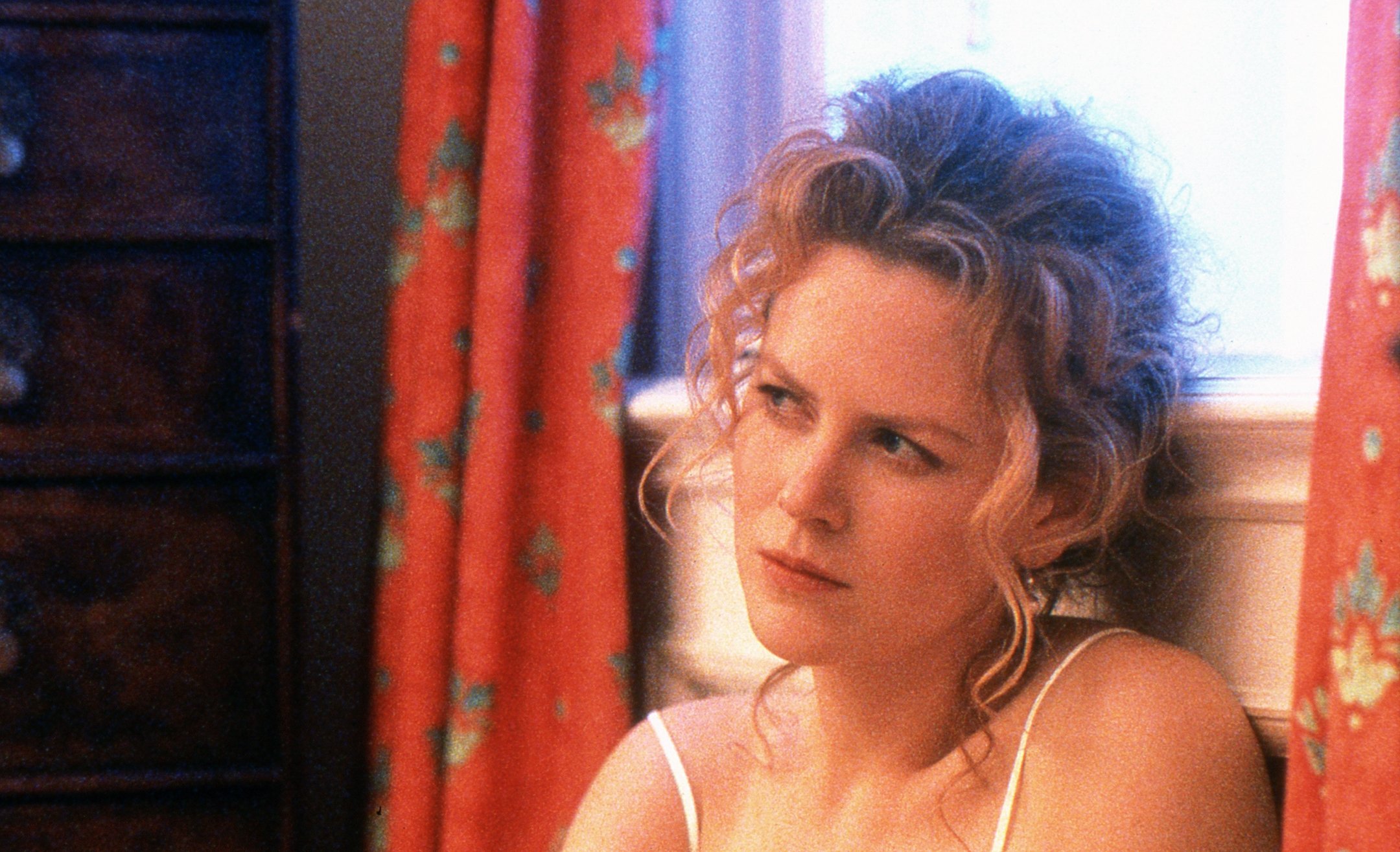

A key aspect of the film's visual design is its meticulous color structure; throughout Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick uses a veritable rainbow of bold colors to underscore the emotional subtexts of various scenes. These hues cover the entire range of the spectrum — the seductive lavender of a prostitute's dress and bedsheets; the warm oranges and deep blues that dominate the Harfords' apartment; the glaring, blank whites of the physician's office; and a crimson red that signals danger throughout the picture, particularly in the orgy interrogator's flowing robes and the felt surface of Victor Ziegler's pool table.

The film's script even seems to make sly reference to this strategy on several occasions: when the two leggy models approach Harford at Ziegler's Christmas party, they offer to take him on a sexual excursion to "the end of the rainbow,' and when the doctor seeks to obtain a mask and cloak for the orgy, he eventually rents them from the Rainbow Costume Shop.

Deluxe U.K.'s Chester Eyre submits that the director "had his own ideas about what each picture should look like, and what he was trying to achieve with it. He had a fixed idea about the color of each sequence, and he would strive with you to obtain that color, even if it had no relation to the preceding sequence. He was always focused on the mood that could be achieved with a certain color. In the case of Eyes Wide Shut, Stanley actually supplied us with information about the red, green and blue [timing] lights. He would look at what had been shot the previous day, mentally adjust the colors, write the specifications on the camera sheets he gave to us, and then request certain color combinations that he'd devised with Larry Smith on the set. Normally, it's left to the laboratory to assess the color of the negative. A filmmaker might ask us to print something a certain way — say, dark and red — but Stanley was asking for specific combinations of colors."

A striking example of this strategy is the Harfords' apartment, with its mix of warm tones and blue light:

Although these scenes were lit mainly by practical household fixtures, Smith used other instruments to add the vivid blue tones. "The blue we used was very saturated, much bluer than natural moonlight would be, but we didn't care about that — we just went for a hue that was interesting," Smith says. "I used open-faced clear glass arcs to get that particular color, and to create shafts of light that would bring out the sharpness of the blinds. It was an over-the-top blue, but it complemented the orange light very nicely and gave those scenes an intriguing look.”

For close-ups, Smith would duplicate the colors with smaller fixtures. "If we were shooting in blue light, we'd use a blue Chinese lantern for the closer shots,” he details. "If we were dealing with the orange hue, I'd simply dim down the household bulbs to get a warmer feeling. Most of the movie is at either extreme — either very rich and warm, or very blue and cold.”

Reflecting upon his collaboration with the one of cinema's greatest directors, Smith concludes, "Working with Stanley was a great privilege, and I'm very thankful that I met him and got that chance. However, I don't think my lasting memories of him will necessarily relate to our interactions on the set. The moments I'll always remember will be those times when we'd be in his office or at the house, drinking some coffee and talking about cricket, football or movies. Stanley had a great sense of humor, and he always had this mischievous little twinkle in his eyes. That's what I'll miss the most.”

Smith's other features include The Piano Player, Red Dust, Bronson, The Blue Mansion, Only God Forgives, Trafficker and Two/One.

Subsequent to the publishing of this article, Smith was invited to join the British Society of Cinematographers, and later became a member of the ASC in 2021.